Marine Geochemistry and Coastal Dynamics Lab

Research Lab Overview

Our coasts have long been recognized for their beauty, natural resources, residential appeal, and more recently for their important position at the core of an ascendant, multi-billion-dollar global tourism industry. This recognition has brought with it decades of investment and economic development that leaves these valuable areas vulnerable in the face of seawater levels, which have been steadily rising across most parts of the world for more than a century. Countervailing pressures between dynamic sea-level changes on the one hand and static economic interests on the other are literally “squeezing” our ocean coasts toward extinction. Our local Outer Banks barrier islands offer no exception, in this regard. Myriad efforts to preserve and protect these valuable areas have been, and continue to be tried to slow, halt, or even reverse the threat, all with varying degrees of success. Successful long-term (21st century) protection, though, will require that we develop a more comprehensive understanding of the natural and human-influenced physical and biological processes at work in these regions so that both the economic and ecological qualities are preserved. From the work that comes before us we know a great deal, but there as yet remains much more to learn about these complex, highly-variable, yet critically important, natural and human-built environments.

I am a quantitative geomorphologist—a geomorphologist studies the Earth’s surface and the geological and geophysical processes at work to shape that surface—with an interest in ocean coastlines and coastal systems. My work is at spatial scales ranging from the continental margins to local beaches. My own, and our Coastal Processes Group, approach blends traditional field and laboratory-based geological and ecological methods with modern in-situ and remotely based sensors, along with classic and contemporary analytical techniques to advance our understanding of these complex landscapes. The natural systems are

themselves multiplex. The situation is further compounded by the addition of anthropogenic forces that work to alter the natural processes and effect change in and of themselves in the coastal landscape. With a development trajectory that has brought urbanization to many coastal regions over the past several decades, humans have become the dominant agents of short and long-term change. In the face of sea-level rise coastal environments and the juxtaposed urban infrastructures, are coming under increasing threat toward inundation. I/we work to understand the natural systems and to further interpret how man’s efforts to counter these threats have altered the ecological and economic dynamic and health of the coastal zone across space and through time.

Contact Information:

Paul Paris

Research Scientist

Integrated Coastal Programs

Coastal Studies Institute

252-475-5430

parisp15@ecu.edu

Current and Recent Research Projects

Beach and Shoreline Processes: Natural and Human interactions:

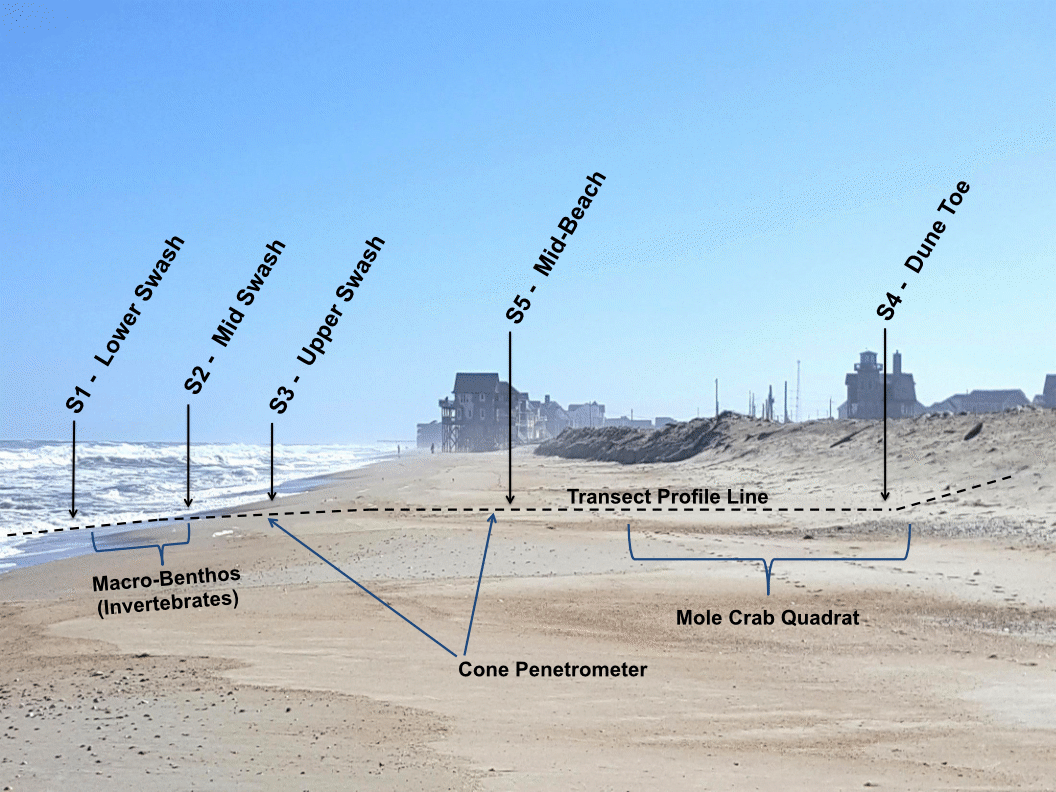

One of the most common responses to storminess and sea-level rise induced erosion along ocean beaches is nourishment. Nourishment, which consists of adding replacement sand to restore the width and elevation of a beach, is thought to be the most cost-effective, environmentally compatible solution to the erosion problem. Given the current state of coastal engineering, it is likely to be the preferred approach called upon to address this problem, both in the present time and for decades to come. The issue with nourishment is, however, that while many of the engineering obstacles have been overcome, we as yet know very little about how it impacts the ecology of the beach—an important element in the overall coastal ecosystem—particularly over the long-term (3 to 5 years or more) and/or with repeated application. Our research seeks to observe, measure, and explain some of these longer-term, little-studied impacts so as to provide coastal managers and engineers with the information that they need to guide future nourishment project designs and contribute to the development of management plans in accord with desired economic, social, and ecological outcomes.

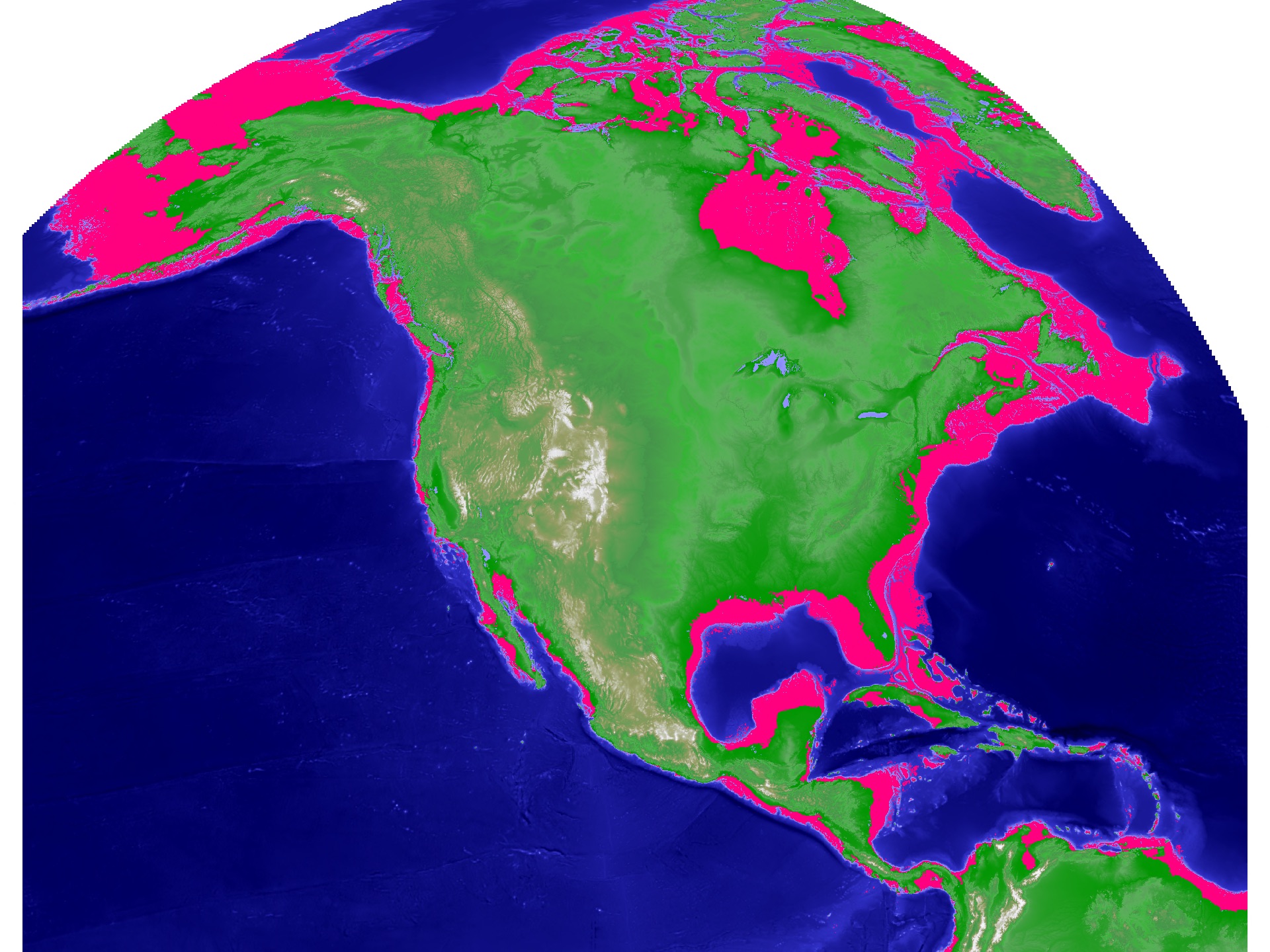

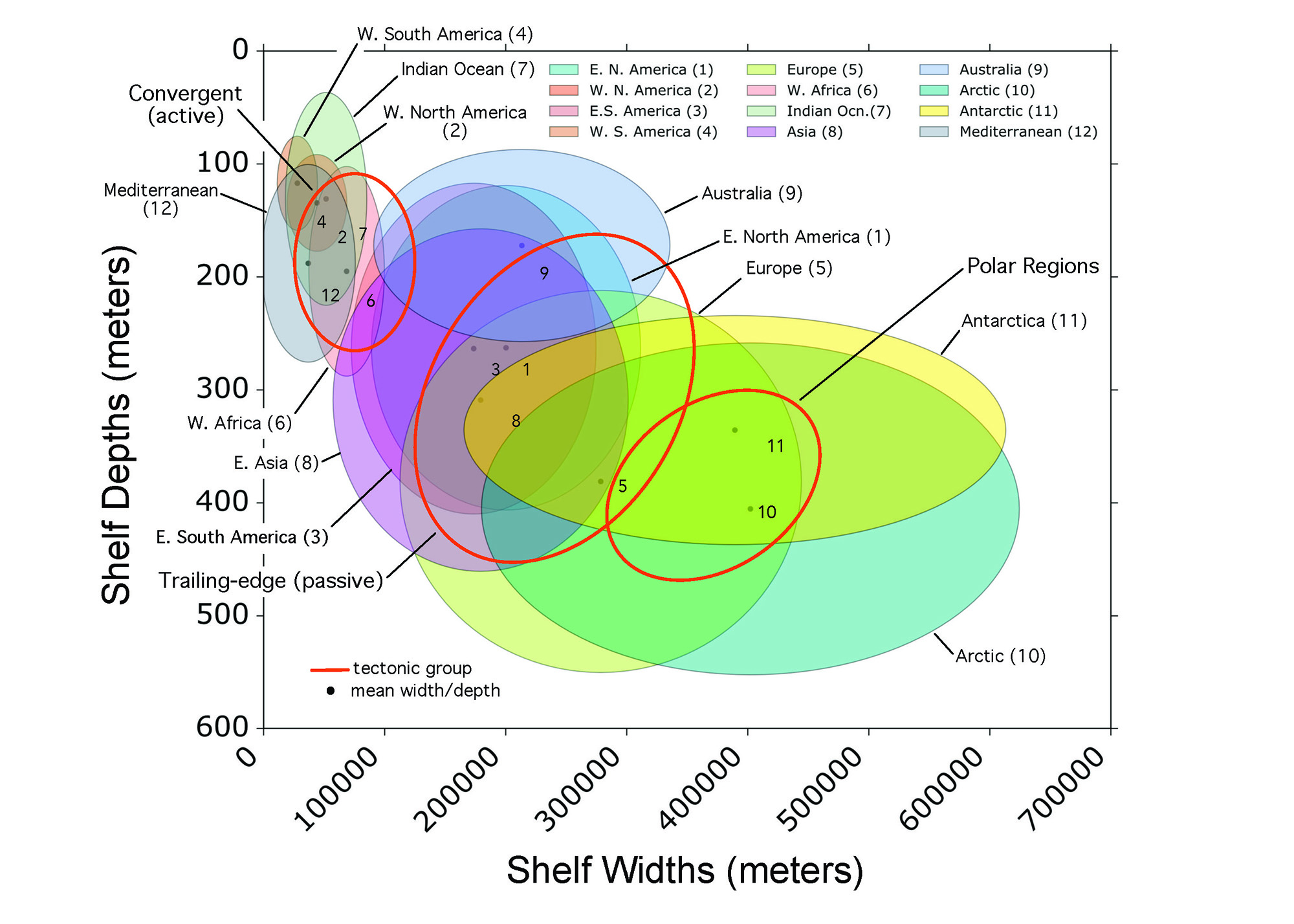

Continental Margin Mapping:

The Earth’s continental margins, those areas from (and including) the continental coastal plains (where they exist), along with the submerged continental shelves, slopes, and rises, are some of the most important regions on the planet. Natural resources abound here in the form of commercial and recreational fisheries, oil, natural gas, as potential sources for alternative energy production, and sandy ocean beaches that sit at the heart of a thriving global tourism industry. These areas, however, are also highly vulnerable to human impacts from sediment and pollutant runoff, waste dumping, dredging, and coastal development. As important as our margins are, they remain as yet poorly identified and mapped. Even along highly populated and well-studied coasts such as those here along the United States’ eastern seaboard, our understanding of their locations, topography, and spatial extents are limited. Our lab and the research it provides is working on ways to identify and map the continental margins, at scales ranging from local (several square kilometers) to global coverage. We leverage traditional bathymetric shipboard and new satellite gravimetric mapping techniques and technologies along with modern machine learning tools to develop novel ways to define, detect, and map these critical environments.

Related Research Focus Areas

Oceanographic

&

Coastal Processes

Marine & Coastal Resource Management

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.