Written by Lauren Colonair.

Physics…but in the Ocean

Dr. Mike Muglia has worked at CSI since it was established in 2003. The journey leading him to the institute has been full of many twists and turns since he began studying marine sciences as an undergraduate at the University of Miami.

“I’ve had a rather circuitous path to getting to CSI, that’s different from your typical academic,” Muglia said of his career.

The adventure really started in his junior year at UM, when Muglia took an algebra-based physics class. Through this class, he was introduced to special relativity and became entranced by the subject. In fact, he was so interested in physics that he requested to change his major. Muglia’s advisor, however, suggested he finish his current degree while taking a higher level physics class, instead.

“But then I couldn’t even sleep, I was so captivated with quantum mechanics and all that,” he said.

To feed his newfound passion, following his graduation from UM, he continued his education at UNC-Wilmington, pursuing a bachelor’s degree in physics. But something was still missing- the ocean. Muglia had grown up around water, and his love for surfing, fishing, and other water-related activities were the reason he studied marine sciences. At this point, he had never been away from the water for such an extended time. The question was, how could a passion for physics be blended with his love for the ocean?

This thought led Muglia to Dr. Harvey Siem, a physical oceanographer, with whom he obtained a Master’s Degree in Physics at UNC-Chapel Hill. The next few years were spent working for Dr. Siem as a lab technician. For Muglia though, studying the ocean wasn’t enough; he wanted to be near it.

“I said, ‘Look I love what we do. It’s fantastic. I just can’t live away from the ocean, so just to let you know, I’m looking for other jobs.’”, reflected Muglia on his conversation with Dr. Siem.

A month or so passed when Dr. Siem approached Muglia with an opportunity he could not pass up. The University of North Carolina was attempting to start a research institute on the Outer Banks and someone was needed to support the ocean observations that were taking place.

“That was my dream job, I always dreamed of living out here and doing something that I liked,” Muglia said.

His time with what would become CSI, started in downtown Manteo, in a building where a parking lot now resides. Like many of the scientists, who have been with CSI since its inception, Muglia helped design the current building. He was even involved in the designs for Jennette’s Pier when it became the institute’s research pier.

Moving forward, Muglia obtained a Ph.D. in Marine Science from Chapel Hill, and he is now a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Coastal Studies at East Carolina University. In conjunction, Muglia serves as the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program’s Assistant Director for Science and Research.

The work Muglia does is centered around many components of the Gulf Stream, specifically the areas which flow off of Cape Hatteras. His group’s scientific research studies the Gulf Stream’s physical oceanography and its interactions with shelf currents, shelf open ocean exchange, and the Deep Western Boundary Current. With the help of modeling groups, these observations are used to understand the dynamics of the Gulf Stream. His group also studies the evolution of deep-water waves as they propagate on the shelf using several buoys to measure the wave field. Muglia is also heavily involved in hydrokinetic research, the study of the motions of fluids and the forces that affect and produce those motions. With the help of engineers, the aim of these projects is to develop devices to harvest energy from the Gulf Stream.

“We try to keep them honest about how the Gulf Stream actually works, not theoretically,” Muglia said of his hydrokinetic work.

The Convergence

The placement of CSI has given Muglia access to a very special area of the east coast. Scientists all over the east coast are interested in this specific area for more reasons than one.

“The silly thing I always say is, Cape Hatteras is like the Mason-Dixon line for oceanography,” Muglia said.

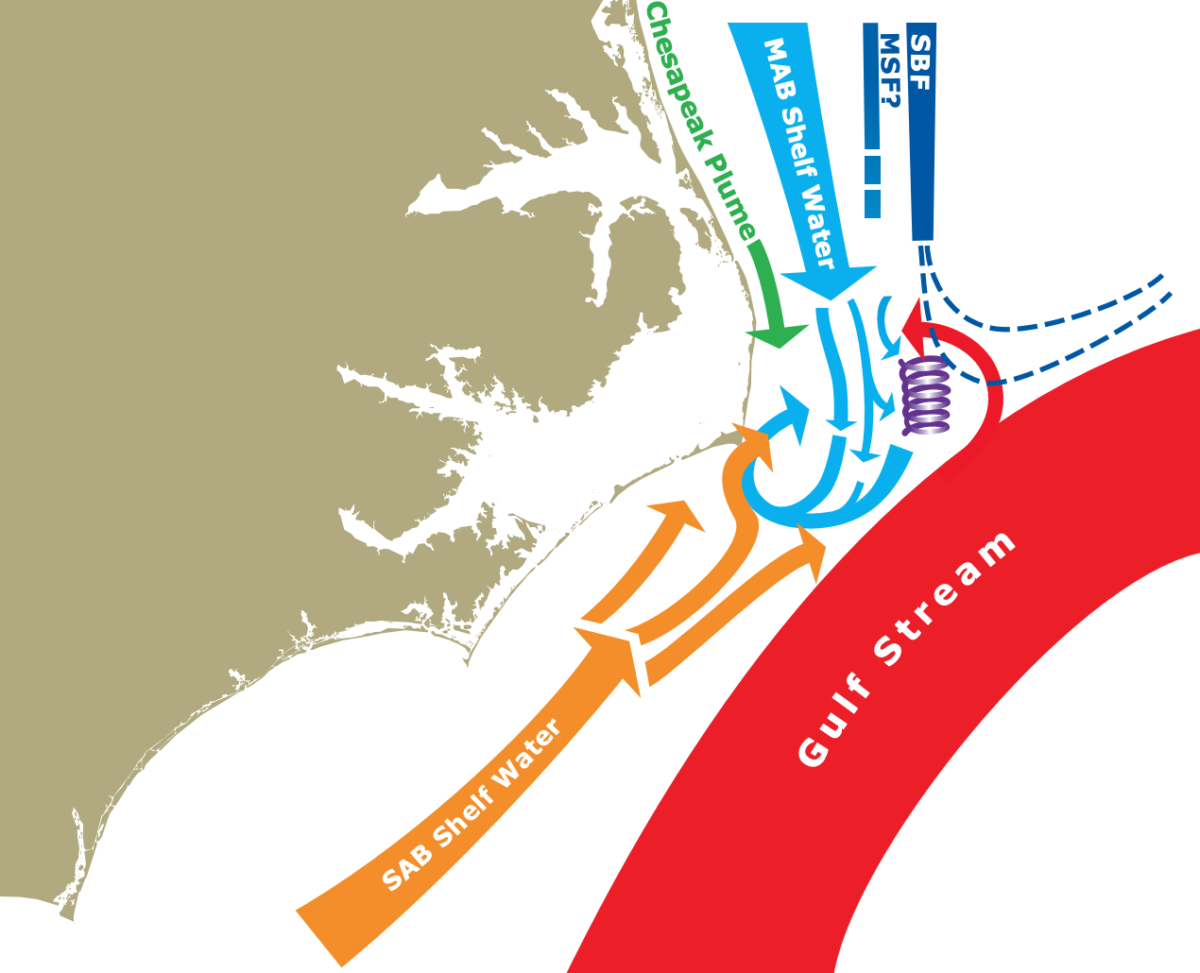

He explained that water currents usually flow along the same depth, or isobaths; however, this is not the case off of Cape Hatteras. On the continental shelf, there are multiple ocean currents converging into one another. From the south warm salty water is generally flowing to the north. In a similar fashion, from the north, cool and relatively fresh water is flowing south. At the same time, the Chesapeake Bay Plume is also moving towards the area in which the northern and southern currents converge. All of this water meets at the Hatteras Front. Here, the water is pushed out and across

the isobaths, where it has the potential to mix with the Gulf Stream. In this same area, past the 100-meter isobath, the continental shelf drops off steeply and another current, the Deep Western Boundary Current, flows under the Gulf Stream. When the Gulf Stream moves off the shelf, the deep ocean water from the current has the potential to be carried upwards, towards the surface.

The water moving off the shelf and from the deep ocean causes high rates of nutrient mixing and sheering, all while the biology and chemistry of these places come together. It is also suspected that high levels of carbon sequestration may occur in this area.

“That’s why it’s such a special place to study, at this big confluence,” Muglia said.

Hypothetically, this area is a good place to harness energy from the Gulf Stream due to its proximity to land, relatively shallow water, and high currents. The stream tends to move around a lot, but off the coast of Cape Hatteras, it moves the least after the Gulf Stream leaves the Florida Straits.

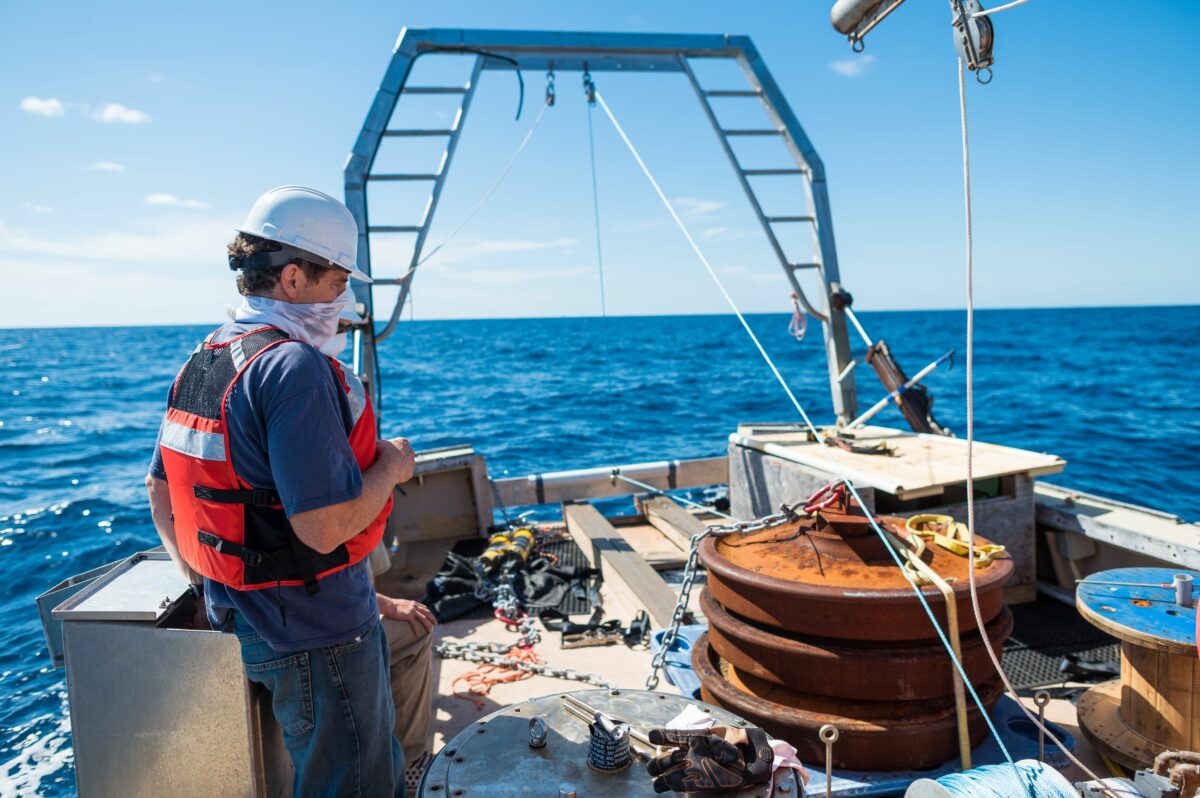

Off the coast of Cape Hatteras, the Gulf Stream is also a treacherous but beautiful place to work. The strong flows of water, in conjunction

with wind forcings, have massive effects on the weather and the state of the sea. Muglia explained that some days the water can be extremely rough while going to the study site, but when he reaches the Gulf Stream, it’s calm. On other days, getting to the study site is a calm ride until they reach the Gulf Stream and then the waves stand up to two or three times the size. Additionally, the quantity of warm water flowing in the area influences the climate meaning, even during the winter, Muglia and his team are often working in summer-like conditions. At times, storms, and even tornados, could be present on the land, while the researchers are experiencing a sunny day out on the boat.

“It’s just magical when you get out there. You see all these critters.t’s just fantastic,” Muglia said of the Gulf Stream. “The water is this crazy color, this deep blue.”

Miss Caroline: The Dream Boat

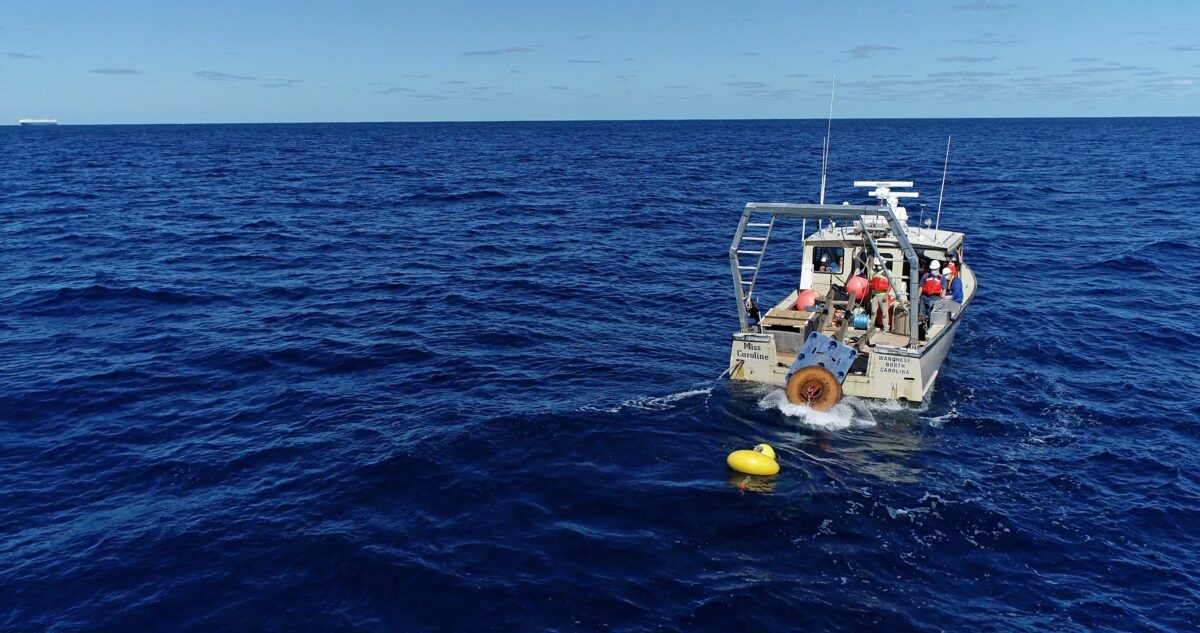

Muglia’s research team relies on observations originally collected in a small outboard boat, along a 14-kilometer (approximately 8.7 miles) transect near the edge of the continental shelf. Once, while giving a presentation to the NC Renewable Ocean Energy Program, he was asked why he didn’t take measurements of the entire Gulf Stream.

“I was like, it’s a really small boat to be where I am. My commercial fishing buddies already think I’m nuts to be out there in that thing,” Muglia recounted.

He was asked what he needed instead, and soon he found himself shopping for a research boat that could do the work of a ship. He ended up finding the “Miss Caroline” in Connecticut. She was the perfect vessel to carry out his work. Unfortunately, the group had to build all of the outfittings they needed on the new boat, a task none of the local boat builders were willing to undertake. After a while, Muglia’s friend and colleague Stormy Harrington undertook the

project and installed an A-frame, hydraulics, custom through-hull Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) compartments, and an equipment-launching sled on the boat.

The compartments are essentially two tubes within each other, which house a 75 and 300-kilohertz ADCPs. When the tubes are lowered, they stick out under the boat and prohibit the bubbles that run down the hull from impeding measurements. These systems allow the research group to take continuous measurements. Miss Caroline is also equipped with onboard computer servers that operate the instruments and archive observations, continuous salinity, and temperature measurements from the CSI dock, all the way across the Gulf Stream.

Many outside organizations have heard about Miss Caroline and contacted Muglia to collaborate on projects. CSI’s research boat can get scientists and their equipment to the Gulf Stream in a few hours at relatively low cost, whereas a research ship would require much more time and money while not being able to traverse the shallow waters of Oregon Inlet.

“It’s not much to look at,” said Muglia, “but it’s a tank to work on.”

All the Scientific “Toys”

Muglia’s research requires the use of many different scientific instruments that require special buoys, moorings, and other gadgets to operate correctly. The deployment and collection of these tools are just another reason Muglia’s boat is so useful.

Waverider buoys are one tool used frequently by the researchers. These buoys measure directional wave spectra, or, in other words, all the different waves hitting the buoy from all directions. Accelerometers inside the instrument take measurements on the number of waves and their directional movement. To allow the tool to function properly, it is held in place by rubber-band-like mooring lines, enabling it to move with the motion of the water.

Muglia currently maintains two of these waveriders and is preparing to launch a third off of Cape Hatteras. The information from these devices is relayed back to the team in real-time and can be used for many projects. Mainly, it assists in evaluating wave energy on the Continental Shelf. The buoys also help evaluate the accuracy of nearshore wave models that estimate the evolution of waves as they propagate on the shelf.

Muglia’s group also uses large pods that sit on the floor of the ocean and subsurface buoys to hold most of the other instruments he implements in research on the stream. The bottom pods have presented some issues to the researchers, thus subsurface buoys have become the tool of choice. Despite the method, the scientific devices are held below the surface, allowing them to take measurements for extended periods of time. To secure the setup, chains are connected and attached to acoustic releases. Following the desired time, the team will send the releases an acoustic signal, and the equipment will then be released from the anchor to float to the surface. Typical deployment depths are 230 meters.

“When I put one of those pods together to deploy, I tell people it’s kind of like throwing your house overboard, hoping that it comes back,” Muglia said of the process.

These setups hold devices such as CTD’s, an acronym which stands for the variables the tool measures; conductivity (for salinity), temperature, and depth. This instrument is what enables Muglia to estimate where the water flowing in the Gulf Stream originated from.

ADCPs can also be deployed with the use of these tools. These devices allow the researchers to measure current velocity around the stream. Data such as this is not only useful in determining the optimal areas for energy collection, but also in mapping the movement of the Gulf Stream itself.

For Muglia, the location of his work, the equipment at his disposal, and his vast knowledge in the field has resulted in involvement and collaborations on multiple projects with various entities. Still, as he

recounted his experiences, he emphasized that his best days are spent on Miss Caroline with his group, simply observing the unpredictable, beautiful Gulf Stream.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.