Coastal habitats, such as seagrass beds, coral reefs, mangroves, and marshes play a critical role in the overall health and resilience of coastal systems. David Lagomasino, assistant professor in the Department of Coastal Studies at ECU and J.P. Walsh, director of the Coastal Resources Center (CRC) at the University of Rhode Island, are working to better understand and characterize these types of habitats as part of a joint research project in the Philippines. Lagomasino and Walsh recently returned the Philippines where they conducted field research over a two-week period. The trip was part of the Fish Right Program, a partnership between the Government of the Philippines and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by the Coastal Resources Center (CRC) at the University of Rhode Island. Fish Right was established to improve marine biodiversity and help better manage fisheries in the Philippines. Lagomasino’s role in the project was to map coastal habitats and how they change overtime, something that he also researches here in North Carolina.

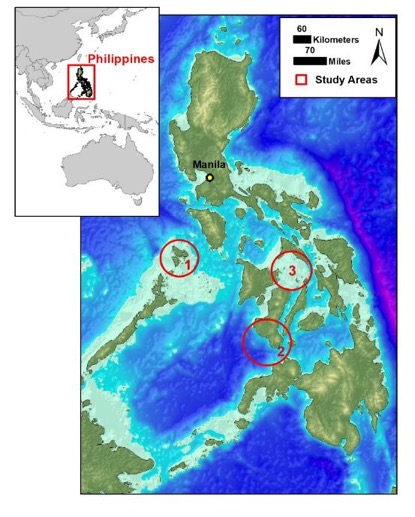

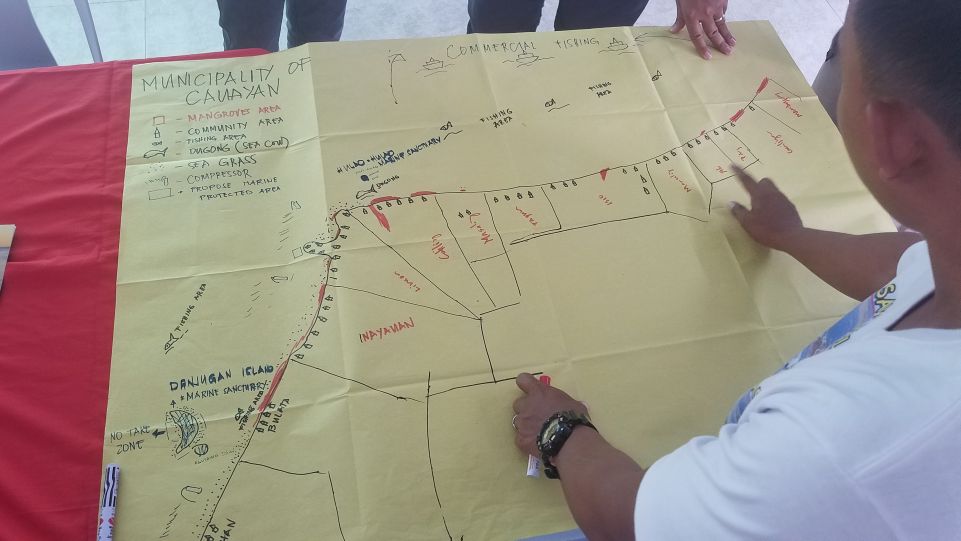

While in the Philippines, Lagomasino and Walsh conducted fieldwork as well as outreach over the course of 10 days. They visited three field sites among two very geographically and geologically different islands, observed and held community meetings and interactive workshops, and gave a talk at Silliman University, a research university in the Philippines. The two distinct islands also each had their own set of threats, so it was extremely important for Lagomasino and Walsh to get to know the communities in which they were working. The local and indigenous people were delighted for the researchers to be there, providing local insight to Lagomasino and Walsh on threats the ecosystems are facing, as well as what areas, fisheries, and issues were important to the different communities. Lagomasino shared, “They were very excited to have us there. They joined us in the field; they were helping out and asking lots of questions. They were trying to learn from us as we were trying to learn from them. It was really an information exchange.”

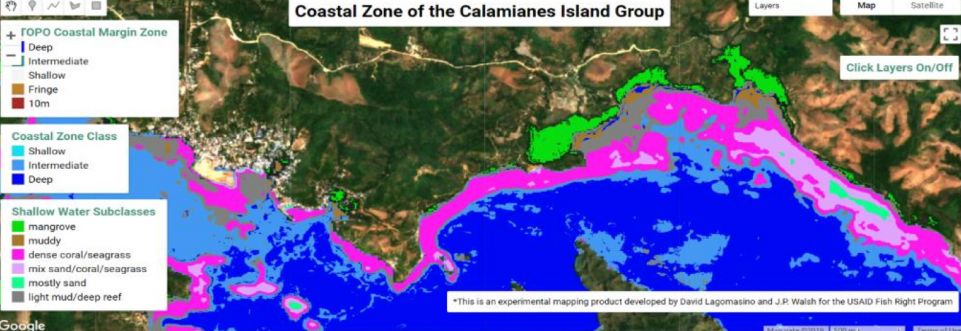

Lagomasino and Walsh collected drone footage, sonar data, and sediment cores to ground-truth the integrated coastal zone maps and models they had produced already for those areas. Their data collection, combined with local knowledge and community interactions, were

important tools used to better understand the entirety of the Philippines’ coastal zones, made up of habitats such as seagrass beds, corals reefs, and mangroves, as well as nearby towns, current threats, and other land-use types. Their work helped validate the previously made maps which will eventually give insight into coastal zone distribution when designing marine protected areas suited for each community. The maps also have the ability to highlight coastal change and threats to specific habitats.

Lagomasino noted an area of interest they first identified on their maps before they ever arrived in the Philippines. “When we initially saw it, we thought it might’ve been the community going into the forest and cutting it, but then we did a time-series analysis and said, ‘Oh no, that happened in December 2013.’ All of it seemed to happen in 2013, so we thought ‘Let’s see the cyclone record.’ That’s when we noticed that Typhoon Haiyan, locally known as Yolanda, went through at the end of November…. We went to those spots, and we now have ground and drone pictures and documentation of the impacts of the event.” While much of the area would have been affected by the typhoon, there are still some pockets that have not recovered six years later. While the local people had implemented restoration measures in their immediate surroundings, they were not aware of some of the deforested pockets until Lagomasino and Walsh shared the maps with them. The locals were shocked and wanted to get more information on how to help the affected areas recover. This opens up new research questions for Lagomasino and Walsh as to why these areas have not recovered and consequently, they now plan to compare the areas that have received restoration efforts by the locals with those that have recovered naturally.

When reviewing his trip, Lagomasino especially highlighted the work that was done within the communities and the level of collaboration with community members. He said, “It’s not that we are just going in, and we’re collecting data, and we’re leaving. We’re going to these communities, we’re meeting with them, we’re working closely with them, we’re exchanging information from them.… We’re really working with them to understand what their issues are and what is important to them.” All of the data that was collected during the trip, once processed, will be shared back to the communities and local decision-makers. Lagomasino made sure that due credit and respect were given, adding, “It’s not our data. It’s really their data, and we’re using it.” While Lagomasino will use this data to create better maps and models and provide the

communities they visited with ample access to it all, he said it is not his place to tell the communities how they should implement their management practices and marine protected areas. Should they ask for suggestions, he said that he could make a few recommendations that are within the realm of his field; however, he believes only a dialog amongst the community will decide the best way to implement management plans based on their needs to incorporate things such as the economy, coastal development, and important habitats for fisheries.

Now that he is back in North Carolina, Lagomasino has had time to reflect on his effort in the Philippines and how it relates to his on-going work both here and in other parts of the world. Part of Lagomasino’s research has focused on the impact of storms in the Caribbean. What he has found there, combined with the results of their work in the Philippines, can help him scale his maps globally. As different coastal areas continue to develop to meet the demands of humans, integrated coastal mapping is becoming an ever-important tool to shape management practices by using a holistic approach instead of analyzing individual areas by parsed out zones like mangroves or urban development. By using integrated coastal mapping, decision makers will be better able to understand the relationships between human development, natural habitat or land change, and the environment. Take fisheries for example. Seagrasses, coral reefs, and mangroves are all important nursery grounds for fish, so it is crucial to understand that the entire ecosystem is connected, and that fish move in and out of different habitats. Thus, policy makers and land managers should not only be focusing on a single part of the ecosystem when making decisions, but should consider the interactions between them.

As for North Carolina and the Outer Banks, Lagomasino says integrated coastal mapping can benefit the area by showing how its environment and habitats are changing. By connecting these pieces together, it can then provide meaningful information to management to say “Your beaches are eroding this fast…” or “You’re losing this much seagrass per year…” and helping them to decide whether there needs to be a means of protection in place. He continued, “If you’re looking at the barrier island retreating or rapid erosion around Oregon Inlet, we can monitor these issues with Earth observations, measure the impact over large areas, and provide that information to management and local communities to say, ‘Okay, yes. We do need to do something about this.”

In future trips to the Philippines, Lagomasino hopes to visit additional field sites and continue the community workshops, highlighting with greater detail the techniques of how the local people could monitor their ecosystems. There are no plans to return to the Philippines as of yet, but

Lagomasino mentioned that the community members have already expressed interest for them to come back. For now, however, Lagomasino is content to be back at home analyzing the data and catching up on some well-deserved rest after his whirlwind trip.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.