Ecologists and anthropologists from ECU and CSI, and the University of Puerto Rico- Ponceare are working on a Puerto Rico Sea Grant (PRSG) funded study entitled, “Ciguatoxin detection and model predictions for use in fisheries management in Puerto Rico,” to better understand the connections between ciguatoxin (CTX) and occurrences of fish poisoning in humans. CTX is a natural neurotoxin which originates in toxic dinoflagellates that grow on coral reefs and is found in some fish caught commercially in Puerto Rico and St. Thomas. One of the goals of the study is to create a food web model and simulation to better predict outbreaks of fish poisoning. CTX occurring in fish tissues at > 0.1 parts per billion (ppb) can cause fish poisoning, often within hours of ingestion. Symptoms include gastrointestinal problems, numbness in mouth and limbs, hot and cold temperature sensation reversals, equilibrium loss, and in some cases, death due to respiration and circulatory failure. CTX biomagnifies in the food web, so that low trophic level organisms (herbivorous fish) that eat the dinoflagellates have small amounts of CTX stored in their tissues, but apex predators (like groupers, jacks, hogfish, and great barracuda) have much more. Using a state-of-the-art cell culture procedures, the study will determine how much CTX is found in fishes at each trophic level, which fish species within certain areas have increased toxins, and where CTX hotspots are likely.

“Because there is no reliable test for the presence of CTX in fish sold by dealers, people are inadvertently exposed to this neurotoxin in some species of fishes,” said study lead investigator and ECU Department of Biology Professor Joseph Luczkovich. “Caribbean reef fish are being consumed by millions of people while on vacation and these fish are exported to the US and Europe. Public health officials are becoming increasingly aware that there is some risk associated with CTX in the seafood supply, but it is difficult for health authorities to assess the risk”. CTX is not inactivated by cooking. The lack of an easy-to-use-test for CTX means there are many cases of fish poisoning that occur unexpectedly, within hours of consuming fish. Symptoms may not be associated with fish consumption and often can be misdiagnosed by emergency responders. Many mild cases of poisoning go unreported. “Our study will help health officials better predict the places, species and times of year when CTX reaches toxic levels, so they can be prepared to respond,” concluded Dr. Luczkovich.

Interviews conducted by ECU and CSI anthropologists David Griffith, Cindy Grace-McCaskey, and Miguel del Pozo at University of Puerto Rico Ponce with local fishers in St. Thomas and Puerto Rico will provide additional insight into local ciguatera knowledge. The goal is to identify any known geographical hotspots, known fish that are high-risk, and how fishers decide what fish to take and not take. The work done by Dr. Luczkovich’s biological assessment team has so far confirmed the accuracy of local knowledge.

Dr. Luczkovich, with the help of scientists at the University of Puerto Rico Humacao and CSI staff, recently collected dinoflagellate

plankton Gambierdiscus sp. strains with varying toxicity from different locations using “collector” screens which are deployed on the seafloor for 24-hrs. The screens were shipped back to ECU and the NOAA Beaufort NC Laboratory for analysis of plankton and algae found at the

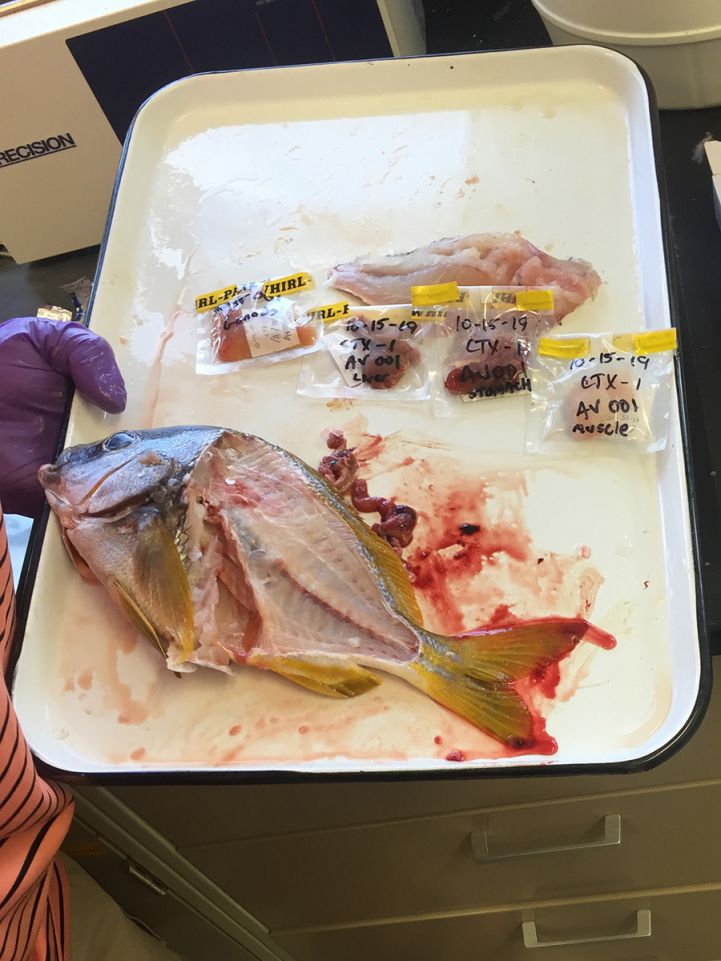

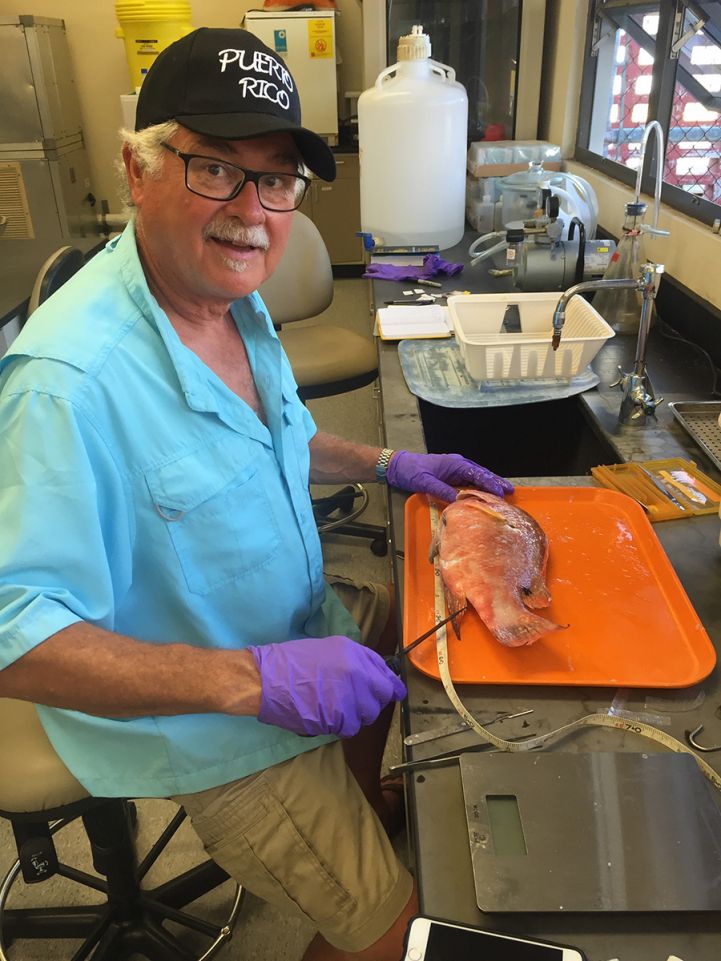

sites. At the same sites as the “collectors”, fish were also collected to link the movement of the toxin within the food chain. Data collected from each fish includes samples of the liver, stomach, gonads, and muscle, which are being tested using the N2A neuroblastoma cell culture technique by Henry Raab, a doctoral student in the ECU Coastal Resources Management Program, for levels of CTX at the Brody Medical School and Department of Biology at ECU in Greenville, NC. The fish toxicity and Gambierdiscus cell count data will be used to provide parameters for the final food web network model and the levels of CTX in the fishes in that area. The Coastal Studies Institute is partnering on the field portion of the project through dive operations and fish data collection by fishing and spearfishing.

Following the data analysis, Dr. Luckovich’s team will use the ECOTRACER simulation routine within ECOPATH model of food webs to provide Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA), USVI Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR), and Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC) authorities information that can be used to monitor CTX and to provide data for consumption advisories. The ECOPATH/ECOTRACER model will be able to input algae cell counts from screen collector samples to predict future problem areas. Identifying local ciguatoxin hot spots will make local artisanal fishing practices safer and should lead to increased consumer trust in Caribbean seafood, higher fishery production, and increased seafood sales. The data from the study will also be used in education and outreach to inform the public and health care professionals about the dangers of CTX.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.