Dr. David Lagomasino, Assistant Professor in the ECU Department of Coastal Studies, does not have the superpower ability to fly, but when it comes to observing the geography and ecology of our coasts, he does have a bird’s-eye view. David is a remote sensing scientist, specializing in the science of obtaining information about objects or areas from a distance. Using airborne platforms such as drones, planes, and satellites outfitted with a range of sensors (e.g., thermal infrared or hyperspectral), he can measure a variety of characteristics: land cover, structural details, height, elevation, and spatial as well as thermal properties. Drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles, are especially beneficial in mapping large expanses of land and remote or hard-to-access areas.

“The captured imagery illustrates on a large scale how fast the world is changing, particularly along the highly dynamic coastline,” says David. “It puts things in perspective by presenting evidence of the interaction between natural systems and human and urban systems,” says Lagomasino.

Data can be used to generate maps of coastal features and wetlands, monitor shorelines and erosion, and chart wildlife habitats. Sharing research and findings serve as a catalyst for informed decision-making to mitigate the damage of urban growth, climate, and natural disasters on vulnerable areas.

Visual and digital analysis of remote sensing datasets is not without its challenges, though. Extrapolating data involves complicated coding, parsing, and scripting. Software bugs in computer programs can make for a difficult and slow process. It is times like these when a break from the computer is in order. David likes going out in the field and doing what is called “ground truth.” In remote sensing, “ground truth” allows image data to be related to real features and materials on the ground and aids in the interpretation and analysis of what is being sensed. This enables him to scale measurements to see if they line up with what he sees in the field.

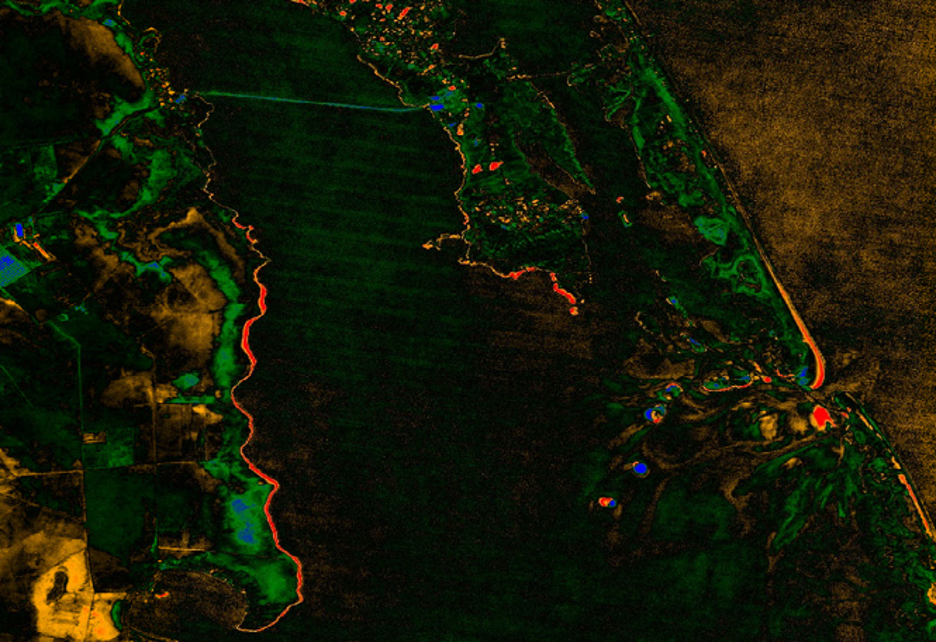

This image above displays land change from 2000-2018 in the area surrounding Oregon Inlet. The scale is from red (land loss) to blue (land gain).

Trees can be measured with drones using photogrammetry, a technique that uses photography to extract measurements of the environment. To take it a step further, stereophotogrammetry utilizes a three-dimensional model based on the positions of recognizable points in different photographs. If imagery reveals that trees in an area are 10 feet tall, David can visit the area and confirm (ground truth) that is truly the case. How does one measure the height of a tree? In the “old days”, a protractor and a good understanding of trigonometry were required. Today, there’s a handy gadget called a laser rangefinder which uses a laser beam to calculate the height in a matter of seconds.

At East Carolina University (ECU), while pursuing his master’s degree in Geology, David conducted research on marsh sedimentation in the Pamlico Estuary. His doctoral research (Geological Sciences) led him to the mangrove forests in the Florida Everglades and the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve (Mexico). He has collaborated on research in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Gabon. “It’s interesting to see how different communities around the world use their resources. They live off the trees, the fish they catch, the oysters. Observing this first-hand really provides a perspective on how these small coastal communities thrive and how important it is to protect that way of life.

All around the world, communities face different problems,” he says. He is concerned about threats posed by human activity, climate variability, the increase in larger communities along the coast, hardening shorelines, and disposal of plastics and nutrients in the water. “The solution is a conscious awareness that these things are happening and determining how they can be corrected.”

Aerial photo of mangrove loss in south Florida.

Recently, David worked on a project regarding global mangrove losses. Mangrove forests are prized for their ability to capture and store atmospheric carbon dioxide. And, just like marshland, they act as nurseries for many fish species and provide storm buffering capabilities. Land conversions in the form of agriculture (rice farms), aquaculture (shrimp farms), and urbanization (manmade) account for much of the deforestation of mangrove wetlands. Preliminary results show a concerning rate of loss. The model processing used on the mangrove project works for marshes as well and was applied with success in the Chesapeake Bay.

In the Department of Coastal Studies, David intends to work along the Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, analyzing the shorelines, applying his knowledge of coastal ecosystems – marsh coast and beaches. He will use remote sensing to determine where things are changing and to identify vulnerable areas in the fishery and human communities. With his knowledge and expertise, he will address broader questions from the communities.

Growing up in Miami, Florida, he enjoyed scuba diving among coral reefs and colorful marine life. Here, he looks forward to checking out the abundant historic shipwrecks. “It will be nice to live near the water and have easy access to getting out on the water,” he says. He prefers reading non-fiction and favors books about geology and stories of the history and legends of local people.

Moving from Maryland, in the DC suburbs, and having always lived in large metropolitan areas, he is ready to embrace a more relaxed lifestyle. David and his data-seeking flying machines should be right at home on the Outer Banks, the birthplace of aviation.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.