It is a fascinating proposition that systems in nature can be utilized to stem the tide (pardon the pun) against nature itself. Such is the case when it comes to adapting to and mitigating the impact of sea level rise, storms, flooding, and erosion. Marsh wetlands, oyster reefs, dunes, mangroves, and living shorelines can provide a buffer from storm surge and waves, therefore increasing coastal resilience and stabilizing shorelines. But wait! There’s more! While these natural ecosystems are busy standing their ground, they are simultaneously providing cost-free services, such as water filtration, carbon sequestration, habitat provision, and support for recreation and tourism. A win-win solution courtesy of Mother Nature herself.

This promising approach, called Ecosystem-based Adaptation, was highlighted in research conducted by Dr. Siddharth Narayan and Dr. Nadine Heck, Assistant Professors in the Department of Coastal Studies. The paper titled “Local Adaptation Responses to Coastal Hazards in Small Island Communities: Insights from 4 Pacific Nations” was published (with co-authors) in the journal Environmental Science & Policy. As stated in the report, “the research is important as there is little understanding of the environmental and social factors that shape local adaptation choices, especially in rural and remote island settings.” Such knowledge is critical when determining effective and locally appropriate adaptation strategies.

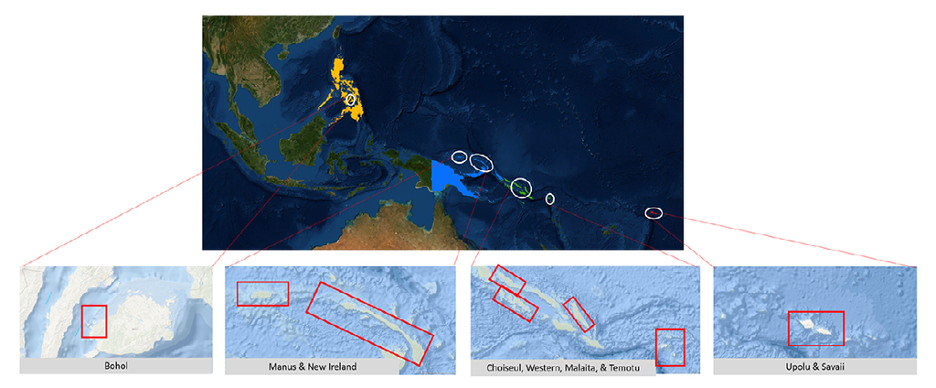

The research focused on 43 towns and villages in four Pacific island nations with most having less than 500 inhabitants and a geographic mix of low-lying atoll islands and coastlines on larger high islands. Confronted with erosion, flooding, and saltwater intrusion (contaminating precious sources of drinking water and affecting soil quality), the livelihoods, natural resources, and cultural heritage are at risk in these surveyed communities:

- Papua New Guinea, north of Australia, boasts dramatic landscapes, with a large swath of unexplored territory. This island of rugged beauty supports a remarkably culturally diverse population with over 800 languages spoken. Villagers rely on fishing in the mangroves and coral reefs for their food, livelihood, and income.

- Solomon Islands lies to the east of Papua New Guinea and northeast of Australia. Here, a mix of the six major islands were studied. Smaller islands (of which there are over 900) have limited space on high ground, making access to many communities difficult. Solomon is a diving hotspot as wrecks of ships and planes from World War II litter the ocean floor. Over 230 varieties of orchids and other tropical flowers contribute to a vivid landscape. The population is concentrated in small rural villages, engaged in subsistence gardening, pig raising, and fishing.

- Philippines is comprised of over 7,000 islands in the western Pacific Ocean, northeast of Japan. Situated on the western fringes of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines experience frequent seismic and volcanic activity, drastically modifying the coastal environment. Land and vegetation are sparse, and the communities studied generally rely on subsistence and artisanal fishing and related activities for their livelihoods. The islands are home to 170 bird species not thought to exist elsewhere, including the national bird, the Philippine Eagle, which at over 3 feet tall is the tallest eagle in the world.

- Samoa lies south of the equator, about halfway between Hawaii and New Zealand. One of the oldest Polynesian cultures, dating back more than 3,000 years, Samoan culture is rooted in a respect for the environment. Coastal fisheries, often located near mangrove wetlands and behind nearshore coral reefs, are an integral part of life in Samoa, forming the basis of livelihoods for many coastal communities.

Countries and locations of study sites. Source: Local adaptation responses to coastal hazards in small island communities: insights from 4 Pacific nations

Speaking with local government and community members and with non-governmental agencies involved in coastal adaptation, data was collected regarding:

- perceptions of vulnerabilities and coastal hazards

- plans to respond to coastal hazards

- implemented adaptation responses

- perceived effectiveness of adaptation responses

- sources of adaptation funding

- incentives and disincentives for adaptation.

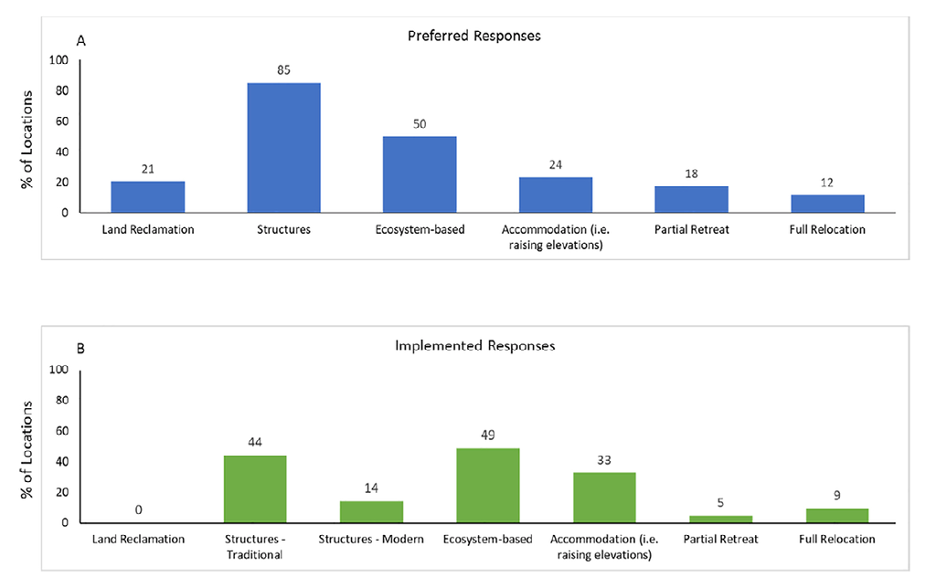

The study revealed that coastal communities view coastal erosion and loss of land as the dominant threat to residential homes and natural assets (such as vegetation and coral reefs), even more so than flooding and sea level rise. So, when considering how best to reduce the impact of coastal hazards, what adaptation strategy was most favored by the government and community members?

Protective structures? No. Hard structures such as seawalls, jetties, bulkheads, and levees are widely preferred but are often not implemented due to a lack of social, institutional, and technical capacity. And, in some cases, these infrastructures are not always the ideal choice, as they redirect, rather than dissipate, wave energy, forcing waves to spill over the structures, providing flood protection to only a certain peak wave height. In addition, they must be updated or replaced to deal with higher water levels.

Accommodative measures? No. Raising home elevations is among the most implemented, although not effective overall.

Retreat (or relocation)? No. The idea of retreat is a highly unpopular adaptation response, and difficult to implement, as coastal communities indicate a strong place attachment, being deeply embedded in their social and natural environment.

Results of preferred and implemented adaptation responses by type. Source: Local adaptation responses to coastal hazards in small island communities: insights from 4 Pacific nations

Ecosystem-based Adaptation? Yes! Dr. Narayan states, “we and our co-authors found that at the local scale, coastal communities in the Pacific prefer Ecosystem-based Adaptation to other strategies for the multiple benefits they provide.”

When societies are given the chance to responsibly and sustainably care for their natural resources, they recognize the complex link they, as well as their livelihoods, have with nature. Prioritizing nature as the first line of defense to reduce the impact of coastal hazards in communities is a strategy that can be implemented using local capital and knowledge, making it an even more favorable option.

Note: This study was supplemented by additional research conducted by Dr. Narayan, colleagues at University of California Santa Cruz, and colleagues in Spain, involving a global-scale assessment of the benefit of mangroves for flood reduction during storms. Their findings were published in Scientific Reports under the title “The Global Flood Protection Benefits of Mangroves.” Evidence revealed that coastal mangrove, marsh wetlands, and offshore coral reefs can protect shorelines by reducing wave heights and storm surges. The article can be accessed here.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.