Coastal hazards, including changing climate, increased storm activity, and rising sea levels threaten coastal communities and the infrastructure they contain. A group of architecture students from North Carolina State University’s (NCSU) School of Design are working on new ideas to increase community resilience through architecture and design. CSI recently hosted these students on the ECU Outer Banks Campus for a gallery-style poster display presented to the local community including coastal scientists, engineers, architects, and governmental officials. The students were a part of Dr. George Elvin’s seminar course on coastal resiliency in which they learned about climate hazard mitigation design and how humans cope with damage from extreme weather events such as hurricanes. The event was organized by Robert McClendon, the Assistant Director for Administration at CSI and NC State School of Design alumnus. McClendon received his master’s degree in landscape architecture from NC State and has sought to keep CSI connected with the university and its design students since the construction of the CSI campus in 2013. While previous students have presented at CSI as well as helped with some landscape design, McClendon was glad to have this group of students here, stating, “it is important to have the students come [to the coast] to learn about the culture of the place because a lot of the solutions they are looking for are things the people here having been dealing with for a long, long time.” However, he continued, “one of the things that is hard to get across to people is that it is as much about the students as it is about the product or the project. So, having the students come here to engage with members of the community is really important.”

There were many different ideas highlighted through the poster presentation including an environmental education park complete with

a boardwalk, voice tour, and small swimming area for children; a waterfront park also meant to mitigate flooding on coastal highways; flood and storm water storage, and treatment systems; extreme weather-resistant building materials; and, finally, adaptable infrastructure aimed to mitigate the loss of life or property damages.

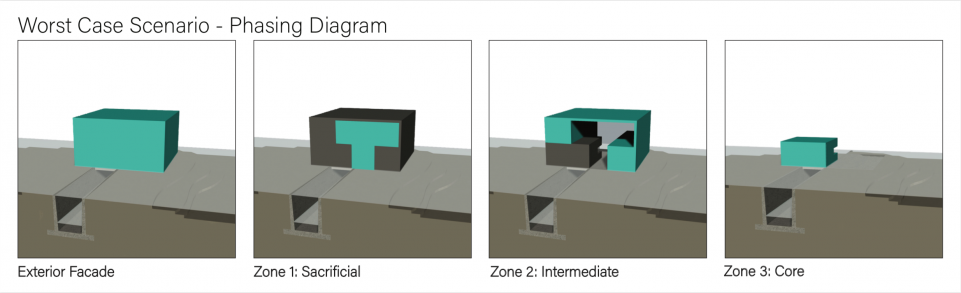

First-year graduate student Marissa Mondin proposed a “Design for Controlled Damage” in which she engineered a house that was built with different zones, each zone becoming increasingly more important and perhaps expensive to replace if damage occurred. Her model was divided into four parts: the Exterior Façade, Zone 1: the Sacrificial, Zone 2: the Intermediate, and Zone 3: the Core. If a house was designed this way and a storm hit, Mondin thought the most valuable things could be saved. Zone 3, Mondin believed, was the hardest and most costly to replace in a “normal” home, would be made of concrete core walls and would offer the best protection for critical infrastructure like HVAC and electrical systems as well as the kitchen and some storage. Zone 2 of the proposed home would be made of a steel frame with steel stud walls and would house bedrooms, restrooms, and perhaps a study or library. Mondin identified these as areas someone would hope to save due to cost or even sentimental value, but that could be replaced if necessary. Finally, in Zone 1 she placed rooms and items that she considered extra and/ or most easily replaced. Those dubbed “sacrificial” included dining, living, and game rooms; an outdoor patio, screened-in porch, or outdoor pool; and the washer/ dryer unit.

While personal perceptions of what is important versus sacrificial may vary from person to person, and though initial costs weren’t necessarily considered for her design, what Mondin placed most emphasis on was the design itself, one that was flexible and adaptable and could help alleviate the cost of damages to a home in a severe storm-prone area like the Outer Banks. The idea for her design was inspired by her understanding of what it meant to be an architect, telling her audience she believed “the duty of an architect as a designer going forward is to design for natural elements that will happen…we can think they won’t happen so much as we’d like, but the world is going to do what it does regardless. And I think it would be to our benefit to not build against those things, but rather invite them into our design process instead of thinking they are a separate entity from our phases of design.” It seems this is the type of thinking that McClendon would like to foster in the students he brings to CSI, ideas that not only end with a tangible product but ones that will also move us as a community forward.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.