These days it seems there is a particular day devoted to celebrating almost anything that comes to mind. While some holidays, like the recent observance of Mother’s Day, are widely recognized, today’s event is likely more obscure to most, though no less relevant to us here at the Coastal Studies Institute. May 10th marks the annually acknowledged National Shrimp Day, so what better day than this to highlight the work of our coastal researchers studying- you guessed it- shrimp?

The Outer Banks is sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine System (APES), the second-largest estuary in the United States. APES is comprised of a number of sounds, one of which is the Pamlico Sound. The Pamlico Sound provides critical habitat for white (Litopenaeus setiferus), brown (Farfantepaneaus aztecus), and pink (F. duorarum) shrimp serving as nursery grounds for each of these ecologically and economically important species. In North Carolina, these three species represent up to one-quarter of the state’s total fisheries landings by weight, and the shrimp fishery is the second most valuable.

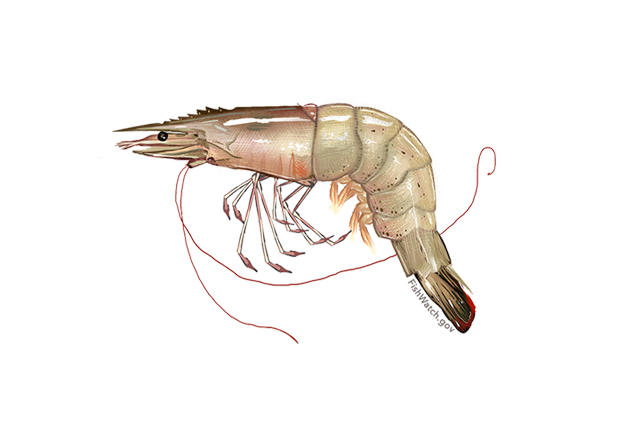

White shrimp, commonly referred to as greentails. Illustration: NOAA.

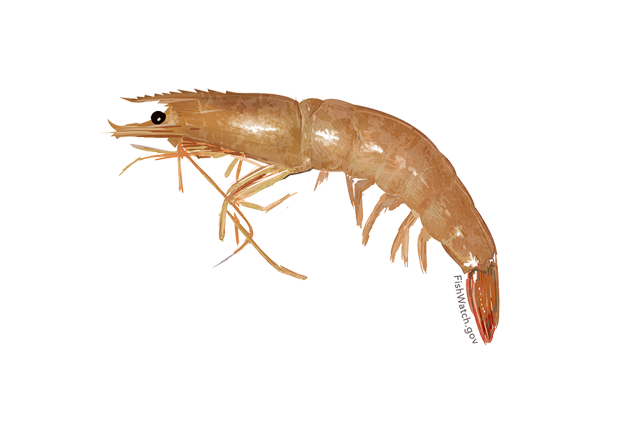

Brown shrimp. Illustration: NOAA.

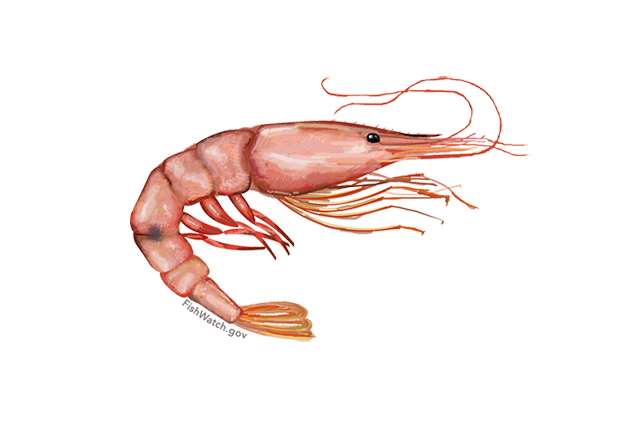

Pink shrimp. Illustration: NOAA.

Despite their importance, the shrimp species are increasingly under threat from impacts of habitat degradation and climate change, and little is known how these factors could affect the recruitment, growth, and movement of shrimp populations. To combat this knowledge gap, Dr. Lela Schlenker (below), a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Marine Fisheries Ecology Lab, is currently using 33 years’ worth of shrimp catch data from NC trawl surveys in the Pamlico Sound and corresponding environmental data to examine, through numerical modeling, the relationship between environmental factors and shrimp populations.

So far, the study has produced some informative results. “The main preliminary finding shows that low precipitation and high offshore wind stress during brown shrimp spawning and recruitment lead to more brown shrimp recruiting in the Pamlico Sound than in years of high precipitation and low offshore wind stress.”, shares Schlenker. She believes it is likely that the same number of shrimp are being spawned each year in the ocean but that the wind and rain affect how many make it into the Pamlico.

Furthermore, while the Pamlico Sound serves as a nursery habitat and though additional models are still in the works, members of the Marine Fisheries Ecology Lab do expect that the climate and environmental conditions will also impact adult brown, pink, and white shrimp.

Just as with many other marine species, it does not seem that shrimp will be an exception from those impacted by changing climate, and because the shrimp are such an economically important species as well, there will certainly be impacts felt by people. Thus, another critical aspect of the shrimp studies are the human dimensions, currently being tackled by Dr. Nadine Heck and Ph.D. student Samantha Farquhar (below) both of the Marine Conservation Lab.

“In addition to the modeling work Lela is conducting, we are actively speaking to members in the shrimp community about their most concerning issues. So far, it has been water quality and changing environmental conditions such as increased temperature and decreased salinity. Shrimpers have noticed that brown shrimp seem to be decreasing in abundance and are now more often targeting white shrimp.”, explains Farquhar.

Once fully developed and finished, the models and community surveys will finally give insight into climate change impacts on shrimp populations and hopefully give fisheries managers important insight for maintaining a responsible, yet lucrative, way forward for the shrimp and seafood industry.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.